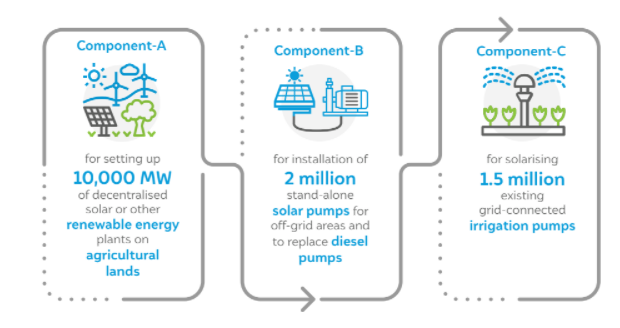

The Indian government has been giving a renewed push to the PM-KUSUM scheme that promises reliable power supply for irrigation. But the proposed solarisation models, especially component A and C that involve grid connectivity have fared poorly so far. A new study by the Council on Energy, Environment, and Water (CEEW) and Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation based on interviews of 15 stakeholders across seven states assesses the state-level challenges of the scheme.

The report “Powering Agriculture in India: Strategies to Boost Components A and C Under PM-KUSUM Scheme” intends to help unlock the potential of two solarisation models – solarisation of rural electricity feeders and solarisation of individual grid-connected pumps – to power India’s irrigation needs. These two models are promoted under components A and C of the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha Evam Uthhan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) scheme launched in 2019. The lead authors for the study are Anas Rahman (Program Associate, CEEW), Shalu Agrawal (Sr program Lead), and Abhishek Jain (Fellow, CEEW).

The study offers the following key findings:

Component-A: Decentralised solar plants on farmlands

Under this model, farmers can set up solar or other renewable power plants on their land (directly or by leasing out land to developers), and the discom would purchase power from them.

Although the component provides long-term economic benefits to discoms, most discoms have surplus contracted capacity and are concerned about the short term disruption in their finances with the additional procurement under Component A.

Under the current policy framework, utility-scale power plants have a cost advantage over the distributed power plants due to better economies of scale and exemption from Inter-State Transmission (ISTS) charges.

Developers are finding the ceiling tariff set for Component-A by many states unattractive due to multiple risks including poor grid unavailability at the distribution level, and payment default risks of discoms. The recently introduced basic customs duty (BCD) on solar panels and cells are also disproportionately affecting its cost competitiveness.

Beyond economics, implementation challenges like delay in land leasing and land conversion approvals stemming from lack of interdepartmental coordination, and difficulties for farmers to access institutional finances are further slowing down the component’s uptake.

Component-C: Grid-connected solar irrigation pumps

Under this model, farmers with existing grid-connected pump sets are eligible for subsidies to solarise their connections, and sell any excess power to the discoms at a predetermined tariff.

This model will bear net benefits for all the stakeholders only under limited contexts depending on factors like farmers self-consumption, extant power supply situation and other agro-economic factors.

States are finding it difficult to get farmers to shoulder the beneficiary contribution under the scheme (40 per cent) in the backdrop of free or subsidised power for agriculture. However, without farmer contribution, the viability of the model gets severely constrained.

In addition, farmers may find the opportunity cost of selling the surplus power high, and prefer to sell water to neighbours or grow more crops (as observed in certain contexts). This would have implications on the financial liability of the discoms and state governments.

Implementation challenges such as metering and billing a large number of dispersed connections and managing the non-participant farmers connected to the feeder make the scheme unattractive for discoms.

Key Recommendations

To stimulate the uptake of Component A, the study recommend the following measures:

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) should consider extending the scheme’s timeline and converge it with the state-level power procurement planning cycle to enable discoms to effectively participate in the scheme.

In consultation with the Forum of Regulators (FoR), MNRE should also prepare a framework for determining the tariff for distributed solar power plants, and consider rationalising the ISTS charges to create a level playing field for distributed power plants.

The MNRE should also consider strengthening the compensation clauses for grid unavailability and payment default under PM-KUSUM to reduce the risks for developers.

State governments need to adopt innovative financing models like farmer-developer special purpose vehicles to address the financing challenges faced by the farmers.

State governments should also form a state-level steering committee to ensure inter-departmental coordination and smooth implementation of the PM-KUSUM.

To support the off-take of grid-connected solarisation model under Component C, we propose the following:

- Pilot the model in different agro-economic contexts to test its feasibility, identify viable financing structures, and study farmers’ behaviour concerning the use of surplus power.

- Discoms should lead the implementation as the component will throw up many challenges that only discoms can tackle. For instance, discoms need to identify and adopt solutions like smart meters and smart transformers to tackle challenges on the metering and billing front, while engaging with the farmers to build trust.

- The MNRE, in consultation with FoR, should prepare a standardised framework in determining a viable tariff for Component-C.

Source: saurenergy.com