With ambitions to become a multinational edtech company, Byju’s has ramped up efforts to develop innovations that will help children learn better as well as extend the reach of such tools to more users. The company has launched an innovations lab project, Byju’s Lab, led by serial entrepreneur Dev Roy, who is chief innovations and learning officer, and based in London.

At home, Chief Product Officer Ranjit Radhakrishnan is also helming multiple projects, one of which is to increase personalisation based on each student’s learning history. In recent years, the company has gone on a blitzkrieg of acquisitions to buy innovative edtech companies and expand its reach in markets such as America.

Early in his career, Roy was a derivatives trader. Later, he was an MD at Barclays and ran the bank’s credit operations in Europe. He returned to India and became an entrepreneur. He built dialysis clinics chain NephroLife Care before turning to his passion for applying technology to education, which he sees as the only way to “scale and attack the problems that are so large compared with the resources we have to address them”.

He founded Digital Aristotle, an edtech company that applied artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to real world problems in education. He sold it to Byju’s last year, and took on his current role. Under his supervision, Byju’s Lab is putting together teams in India, the UK and US. The company announced the lab initiative on October 5.

“What we are trying to do is take deep unsolved problems, often within edtech, and solve them,” he tells Forbes India from London. “These are moonshot problems and we are looking to disrupt ourselves internally so that we avoid the fate that a lot of companies face by being disrupted externally.” As part of this project, Byju’s is looking to attract the best and the brightest minds—typically with PhDs in AI, machine learning, computer vision, gamification and so on—around the world to attack these problems.

For example, if a child siting in Chhattisgarh or somewhere in Indonesia or even in the US can write an answer, take a picture and has access to a system that can machine-read the picture and come back with feedback straightaway, it would be a valuable tool for children in places where good teachers aren’t available. The machine-learning system would have been trained by the best teachers in the world. “Then you democratise education by over-indexing on technology to compensate for the lack of good human teachers,” says Roy.

At the moment, the state-of-the-art AI in edtech can answer questions at the level of the fourth-grade syllabus, he adds. If that capability can be elevated to, say, 10th grade, that would make a big difference to many children who don’t have access to good human teachers.

It will also help us gain a much greater understanding of how children learn, and offer “deep personalised interventions” because children learn in different “multi modal” ways, including not just text, but videos, audio and classroom teaching, of course. The innovations at Byju’s will also be aimed at ensuring that children are offered the modes of learning that they like best without the friction of context switching.

Personalisation and technology in general, in the field of education, are in their infancy, Roy says. It is ripe for the arrival of the edtech equivalent of the BERT model in natural language processing, he adds. He is referring to the ‘bidirectional encoder representation from transformers’ model that researchers at Google suggested in 2018 for natural language processing, which was shown to be very accurate in many tests of natural language understanding.

“Those are the kind of things that we would like to be at the forefront of and contribute to in the field of edtech,” says Roy. Doing that also has the added benefit of projecting Byju’s as a leader in not only online learning but in solving some of the fundamental problems associated with learning.

Radhakrishnan joined Byju’s in 2015 and has seen the entire journey of the company from an offline teaching effort to an online powerhouse of content delivery. Teams are organised as ‘pods’ and are often cross-functional, and they come together to attack specific problems, Radhakrishnan says. These can be specific short-term problems around specific features of a product or a new product line, or longer-term ‘foundational’ problems, he adds.

For example, “personalisation is very close to my heart”, he says. How does Byju’s understand where any given student stands on her learning curve, and based on that understanding, offer the best way forward in terms of content and mode of learning as well—visual or audio or experiential, for example.

“What we’ve done with our entire ecosystem is that all of our content has been mapped to what we call a knowledge graph,” says Radhakrishnan. That universal knowledge graph gives the relation between any two pieces of content and, therefore, the indication that if a student has mastered one, what will she be able to navigate next. Today, Byju’s is able to build learning profiles for individual students, and based on those make different recommendations to different students, he says.

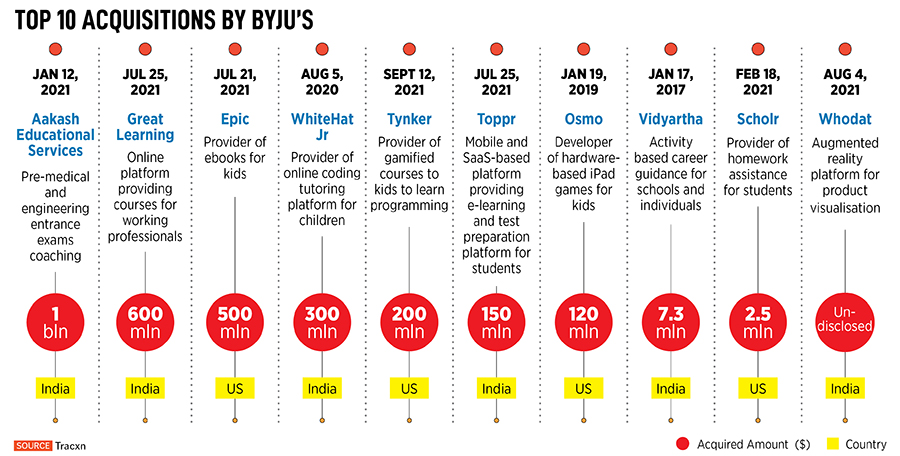

Byju’s has more than 100 million users with 6.5 million paid customers, according to the company. The edtech company, India’s most valuable startup, is also rapidly expanding overseas via acquisitions. In early 2019, Byju’s acquired Osmo, a Palo Alto-based maker of educational games. In July, the company announced the acquisition of Epic, an online digital reading platform provider in the US, in a $500 million deal.

In September, it said it was acquiring Tynker, a coding platform for children in the US, to accelerate its expansion in America. Tynker’s creative coding platform has been used by over 60 million children and 100,000 schools in 150 countries. Byju’s expects to invest $1 billion to expand its US operations over the next three years.

Source: forbesindia.com